Is $1.3 trillion invested in the investment-equivalent of dog crap? Yes; and we are not talking about manure farm I.P.O.s.

This money rots in high-fee, low-performing mutual funds hawked by conflicted financial salespeople. More than 8% of industry assets remains in the two priciest quintiles of annual fees, according to Morningstar Direct.

Where is this money coming from?

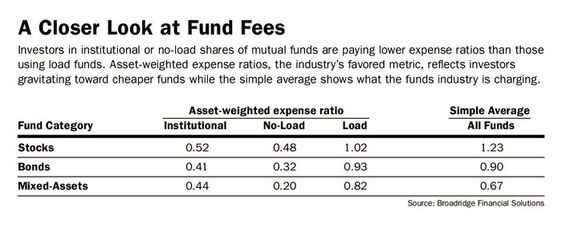

Reshma Kapadia’s article, “The Great Fund Fee Divide,” provides the answers.

“For the most part, the industry’s priciest funds are in accounts that are too small to get much attention. Sometimes they’re in the 401(k) plans of small businesses. Sometimes they’re in target-date funds. Sometimes they’re simply in portfolios with less than the $1 million needed to command the attention of advisors.”

They also find a comfortable home in public school teachers’ 403(b) plans; all of the usual suspects for egregious financial exploitation. In a 2018 world, filled with almost free low-cost index products, this is unfathomable. Why does this occur? Two reasons: price gouging and thousands of share classes.

Investors must pay a fee to the fund company, called an expense ratio. Investors in the priciest funds pay way too much. Often active managers will simply shadow an index like the S&P 500. They garner lower returns but charge 10 times as much as lower-cost alternatives. This is called closet indexing.

According to Charlie Munger, “[With] closet indexing… you’re paying a manager a fortune and he has 85% of his assets invested parallel to the indexes. If you have such a system, you’re being played for a sucker.”

In spite of the fact that active managers charge a premium for their services, almost none of them consistently match the returns of a corresponding index.

Fund companies and their salespeople target the financially illiterate who trust emotions more than math. There are less than 5,000 traded stocks but 8,066 mutual funds; don’t ask.

It gets worse.

According to Reshma: “But when you tally up the various iterations of each fund, there are more than 25,000. Share classes are essentially financial agreements between the fund company and the distributor of the fund (a broker, advisor, or retirement plan). As a result, investors can pay very different prices for the same fund depending on which share class they’re in.”

This scheme is ground zero for financial abuse.

Slick financial salespeople have incentives to peddle funds they collect commissions from. Cheaper versions called institutional shares might be available. Salespeople avoid these like the plague.

Inexplicably, many investors pay an upfront sales charge to purchase a fund. Many of these products come with high expense ratios of 1% or more.

This destroys the argument of conflicted financial salespeople that buying a loaded fund is cheaper than working with a real financial advisor, who charges based on a retainer fee, hourly fees, or a fee for assets under management.

Investors do not know there are cheaper alternative share classes. The industry would like to keep it that way.

It’s impossible to view financial services as a respectable profession with this deliberately convoluted and manipulative system in place. The reason: it is confusing and non-transparent to charge people unnecessary fees.

I defy anyone to explain, in an unbiased fashion, why we need over 8,000 mutual funds and an astounding 25,000 share classes?

Investors can shoulder part of the blame. They are complacent and rely on inertia rather than data. Maybe it will take a bear market to liberate the unfortunate 8% trapped in this fee hell.

“There is a lot of inertia in this business. If a fund firm can get someone to pay an extra 1% and sit in that for 20 years, there is a lot of money at stake; though we are seeing price compression, it is uneven. The extended bull market has made people complacent. When the market goes down, investors tend to turn more fee-conscious.” Barron’s

Will this be the saving grace when the next bear finally does arrive?

We can only hope.

Source: “The Great Fund Fee Divide” by Reshma Kapadia, Barron’s