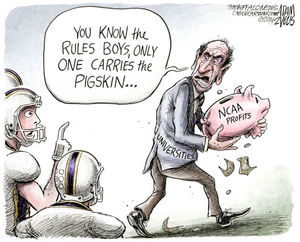

What do many college athletes and brokerage clients have in common? They are both victims of financial exploitation.

Degree-less athletes and fee-ravaged brokerage clients are the outputs of two broken systems.

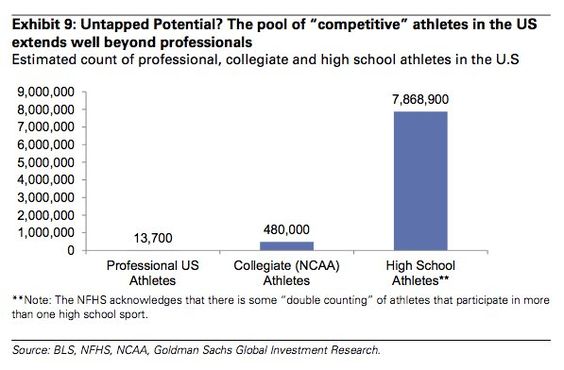

The majority of college jocks will never make it to the pros.

According to Jason Gay of The Wall Street Journal, “A few years back, the University of Oregon unveiled a football complex (largely bankrolled by Nike honcho, Phil Knight) that looks like a Bond villain’s lair and includes a barber shop, farm-to-table dining, and a coaches’ hydrotherapy pool.”

The University of Florida piled on. “More recently, the University of Central Florida unveiled a plan for an athletes’ village that would include, among other flourishes, a “lazy river”—one of those winding amusements you might find at a water park.”

Schools dangle these perks as bait to lure future recruits. This increases their chances of claiming some of the $1 billion dollar bounty that CBS recently paid to televise March Madness. It will also arm them to compete for other outlandish media packages.

Big money is used to entice “name” coaches but does little to improve the educational environment. Players receive video game consoles and sleeping pods; small remuneration for attracting millions of eyeballs which generate hundreds of millions of dollars.

Some argue players receive scholarships which could be worth over $200,000; a mere pittance compared to what schools earn from their exploits. This is not exactly an efficient market.

Many leave school without a degree.

According to Josh Rosen, a quarterback at UCLA, “Any time [a] player puts into school will take away from the time they could put into football …They don’t realize that they’re getting screwed until it’s too late. You have a bunch of people at the universities who are supposed to help you out, and they’re more interested in helping you stay eligible. At some point, universities have to do more to prepare players for university life and help them succeed beyond football.”

What does this have to do with brokerage clients?

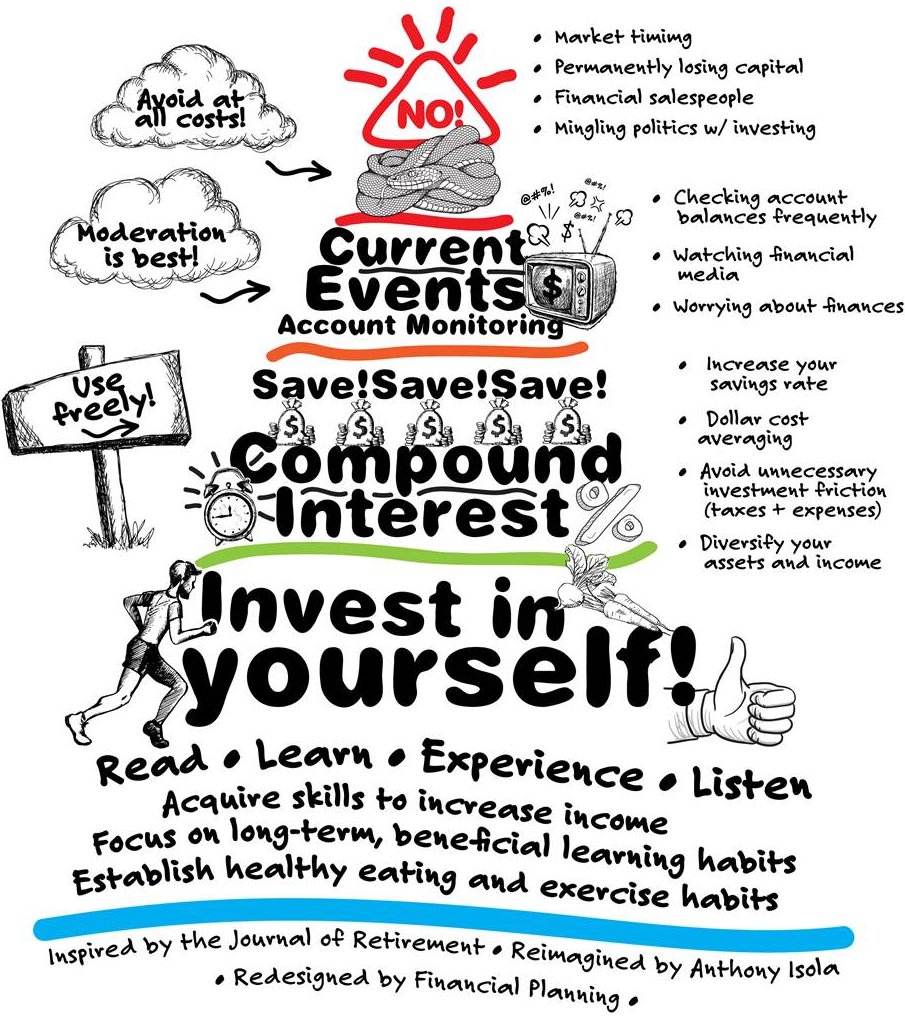

Brokers collect fees, like revenue sharing. Mutual fund companies pay them to subsidize the costs of distributing their funds.

This creates incentives to sell products that pay brokers the most money or perks.

According to Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal, “The fees can pay for data analysis, meetings and conferences, educational and marketing materials, seminars for clients and so on. Similar payments defray the costs of brokers’ and advisers’ hotel bills, meals, entertainment and travel expenses at sales and training events.”

Edward Jones, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch make gobs of cash from these types of arrangements. This accounted for almost 20% of Edward Jones’ revenue in 2014.

The Fiduciary Rule could stop this in retirement accounts. Unfortunately, there is too much political uncertainty to count on anything happening in the near future, if at all.

Brokers swear revenue-sharing arrangements have no effect on what funds they sell.

According to an Edward Jones spokesman who spoke with Mr. Zweig, “I can tell you with absolute certainty that it doesn’t give them an advantage in terms of what gets approved or what people buy or sell within our firm. It just doesn’t.”

Yes, and pro wrestling is real and the Washington Generals have a chance to beat the Harlem Globetrotters.

Like college athletes’ relationships with universities, brokerage clients are often given the short end of the stick.

How about finding different partners to share revenue with? Long suffering customers and revenue-generating college players are excellent candidates.

Brokers use these profits to gather more assets. Schools apply them to recruit talent and pay coaches million dollar salaries.

Student athletes and brokerage clients are providing the capital for these organizations to expand and profit.

Are both investment returns being shared in an equitable manner for all stakeholders? No, not at all.

Investors are left with lower account balances. Student athletes may be left with nothing for their sacrifices if their sports schedule prevents them from graduating, not to mention what might happen as a result of career-ending injuries, or more debilitating long-term effects, like brain damage.

Conflicts of interests can never be completely eliminated.

We can at least try to get rid of two of the most egregious examples.

Sources: The Wall Street Journal; “Stop Giving College Athletes Million-Dollar Locker Rooms. Start Paying Them” by Jason Gay, and “Mutual Fund Fees: A Bad Incentive Fades Away” by Jason Zweig.