Disclosure does not – and will not – protect investors from financial predators.

The SEC is working on Regulation Best Interest to replace the Department of Labor’s defunct fiduciary rule. It is a loose interpretation of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, and is a big bet that hopes to protect investors because the bad guys will disclose their conflicts of interest.

The fatal assumption is that investors will understand the legalese and misleading statements (carefully crafted by these firms’ sharp lawyers). John Q. Public doesn’t grasp the critical difference between advisors acting as a fiduciary versus the newly-proposed best-interest standard.

Kleimann Communication Group conducted an extensive report confirming this for the AARP, Consumer Federation of America and the Financial Planning Coalition. The content was based on proposed customer relationship summary disclosures provided by brokers and others conforming to the SEC legislation. The study’s goal was to analyze answers to related questions and determine if the new disclosure rule would safeguard investors from predatory behavior.

These questions included amongst others:

• Does the investor understand the differences between Broker-Dealer Services and Investment Adviser Services?

• Does the investor understand the difference in Standard of Care between the two types of services?

• Does the investor understand that Broker-Dealers provide no on-going monitoring of the account?

The disturbing results were summed up by Barbara Roper, director of investor protection at the Consumer Federation of America:

“In area after area tested, participants didn’t just fail to fully grasp the information provided — time and again they walked away with a false understanding of the issues, if the disclosures fail, the entire regulatory approach fails.”

The key findings of the report were:

- Most participants did not draw a parallel between the “best interest standard” of the Broker-Dealers and the “fiduciary standard” of Investment Advisers.

- Few participants could define “fiduciary standard.”

- Nearly all participants saw incentives as merely a well-established “way of doing business” and did not object as long as their interests were placed first.

Many actually believed that the best interest standard was better than a fiduciary obligation since it would bring them higher returns.

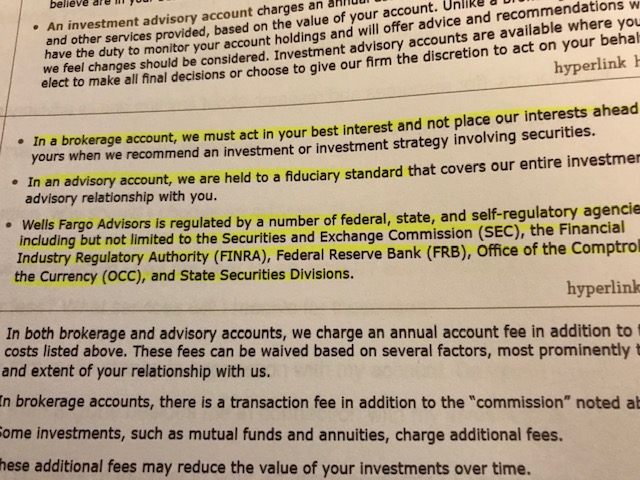

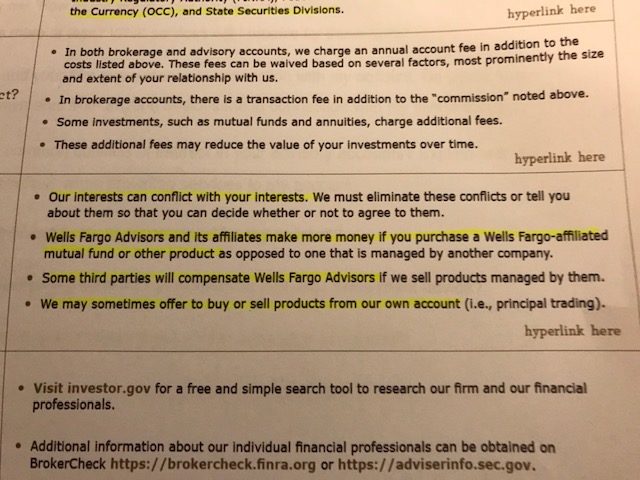

Take a look at Wells Fargo’s proposed CRS and you can see why they might make this assumption.

According to their proposed example, the broker model looks pretty good when the term “best interest” is inserted. It sure sounds much better than the suitability standard.

In addition, many people questioned in the report thought that this account was “safer because so many different regulatory bodies were overseeing it and keeping watch over their money.”

This would be analogous to trusting an inmate at a maximum security prison with your financial future because there are so many guards there. This is not exactly optimal criteria for choosing an advisor.

The lack of understanding by consumers can be summed up by this comment found in the report:

“It sounds like [the brokerage account] wants to hear from you. They give

you the facts and they say do you want to invest in this or not invest in this? . . .

It seems like they would go to you and tell you these are your choices. What

are you thinking? Do you want to invest in this? It has a higher yield or higher

percentage rate and then they ask you what’s your decision.”

Clearly, this portion of Wells Fargo’s proposed CRS was either not read or misunderstood:

It’s no wonder broker-dealers and their lobbyists back a disclosure-based proposal compared to a fiduciary rule that enforced a strict interpretation of the 1940 Act.

The game isn’t over until the fat lady sings.

It sure looks like it will be the same old tired song for investors.