“[With] closet indexing….you’re paying a manager a fortune and he has 85% of his assets invested parallel to the indexes. If you have such a system, you’re being played for a sucker.” – Charlie Munger

Investing is hard even if you know what you are doing.

Week number two of my investment class was devoted to proving this theory.

I started by showing my students how to use BrokerCheck. This is on the FINRA site and is a way for investors to monitor broker behavior. I explained to them that one violation may be an outlier; several are a pattern. It is rare you find just one cockroach in your kitchen.

All kinds of ugly things have reared their heads in broker searches I have conducted from client shenanigans, personal bankruptcy, assault charges, and domestic violence issues.

I told my class, “Look at your broker’s employment history. Frequently jumping from one small firm with a less-than-stellar reputation to another, is not a positive development.”

On the same site, we moved on to the Tools and Calculator section. Using the Fund Analyzer, I showed the students how to determine if they were getting their money’s worth with their investments.

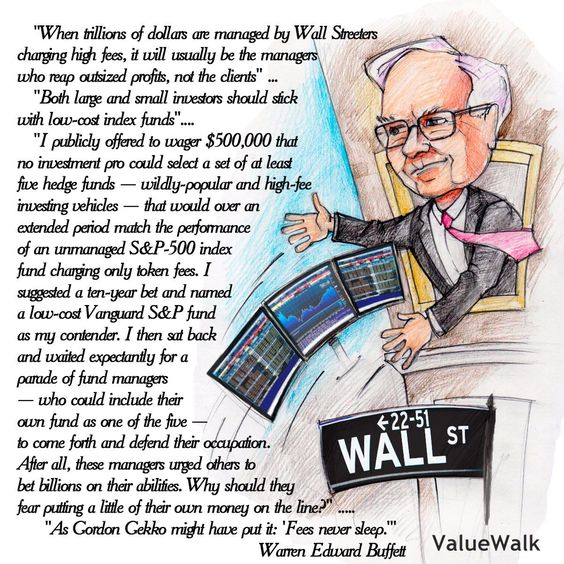

It’s easy, really: Type in a fund you currently own and compare it to a similar index over an extended time period. If the results show the low-cost index is providing superior returns to your fund manager, it is time to make a change.

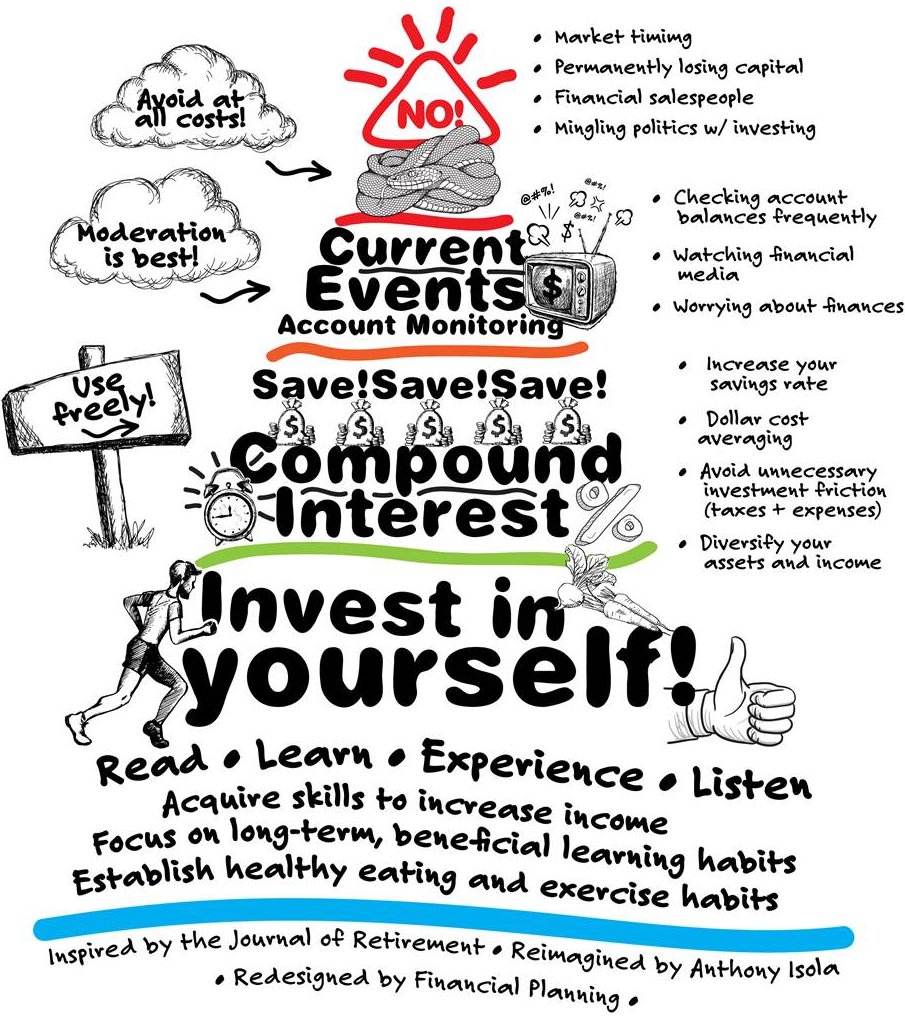

Some funds are called “closet indexers.” Basically, they charge a premium to mimic most of the holdings of a basic index. This provides no added value to you. It provides protection for the fund company against dramatically under-performing the market. It also enables the fund company to make more money to distribute to shareholders or provide large bonuses to upper management. All of this off your backs.

This little tidbit resulted in many groans from the peanut gallery.

We then got to talking about some fund managers who were worth the extra money. Peter Lynch came to mind. Many of the students knew who he was and became excited. I explained to them, “Peter Lynch managed Fidelity’s Magellan Fund from 1977-1990. The average return under his stewardship was an astonishing 29.2%; doubling the return of the S&P 500 over the same period.”

Someone asked, “Is this something we should be investing in today?”

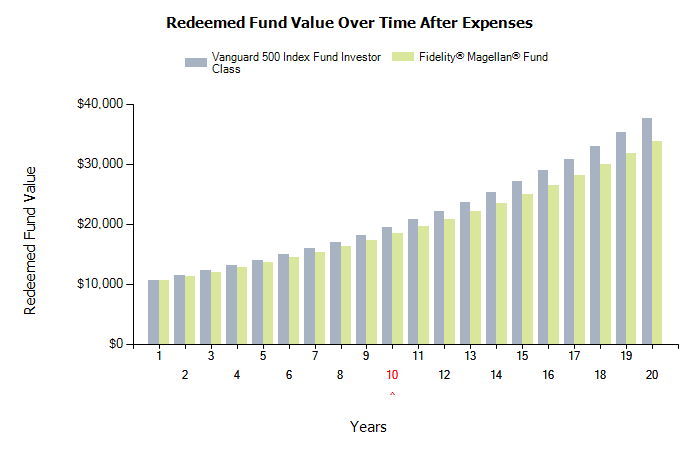

This was a job for the fund analyzer. We compared Magellan to Vanguard’s S&P 500 Index Fund. Assuming a $10,000 investment and a 7% annual return for both over the next 10 years, the answer was no.

The Vanguard Index would leave you with $37,628 while Magellan lagged at $33,776. We assumed this fund would mimic the market’s return over the next decade, minus fees, because of its similar holdings.

Was this a correct assumption? It turns out, yes and more.

Using the Fund Analyzer, we discovered over the last 10 years, after fees, Magellan returned 5.86% annually. Vanguard’s Index fund produced a 7.49% return. This was 28% less than the index due to investment friction, like fees and trading costs. This would reduce Magellan’s numbers to $27,093, assuming the next decade is similar to the last. Investors would sacrifice $10,000 on a $10,000 investment for no reason, other than overpaying Magellan’s fund manager.

Lesson learned. But then a student noticed the fund’s return since inception. Magellan came in at a stellar 15.89% while the index trailed with 10.98%.

Interesting point. I asked the class, “Can anyone think of an explanation for this?” Silence.

I prompted them with, “Is Peter Lynch still there?” They responded with a resounding, “No.”

They quickly realized the possibility that all of this outperformance was front-loaded and after Peter Lynch left things changed dramatically.

In essence, buying the fund based on these numbers means paying for something that already happened, which provides no benefit to the new investor.

Mission accomplished; and now they understand that even when using data to make decisions, you can still run into problems.

Hopefully, my students will get out of their own closet index funds. Knowledge is not power without action.

The moral of today’s lesson: Don’t let your fund company play you for a sucker.