My senior year of college wasn’t filled with the dread that some of my classmates seemed to carry. All the “countdown” parties went on without me; I didn’t feel the need to squeeze the last bit of juice out of my carefree days as a student. I was itching to get on with it; the next big event in my life was hovering on the horizon and was taking forever to arrive. I was impatient for my real life to begin.

Had I not been so doe-eyed, I might have clung to every moment of what was slipping through my hands. I might have even curled up in the safe arms of another university to pursue a master’s or law degree. But I was arrogant, ignorant and without a plan. What could possibly go wrong?

It was the spring of 1987 when I graduated. As my initiation into the business world, I went to various personnel agencies with the same results. My fanny was promptly plunked before an electric typewriter and I was asked to type as fast and as accurately as I could in a minute. No pressure.

I tried to tell them that there was some mistake because I had a degree; if my typing speed was a determining factor for employment, I was in deep trouble. I looked to my left and I looked to my right – no guys were on the typewriters. I guess this was a sign of the times.

I finally landed a job where my boss didn’t care how quickly I typed. The only problem was within five months of starting this job and renting an apartment, the market crashed. Many people lost their jobs as financial firms seemed to tumble like dominoes.

Being entry level, I was cheap labor and I managed to never be without work; yet, I also felt trapped into staying where I clearly didn’t want to belong. But rent, bills and student loans were my responsibility, and I was raised to always meet my responsibilities (even if I felt like a trapped mink, ready to gnaw off a body part just to get free).

What did I have to complain about anyway? I was 22, living on my own, paying my own way and I was employed. This was no time for a pity party, but there was time during my hellish commute to lower Manhattan to fantasize about winning the lottery and buying my freedom from this mundane life I was living.

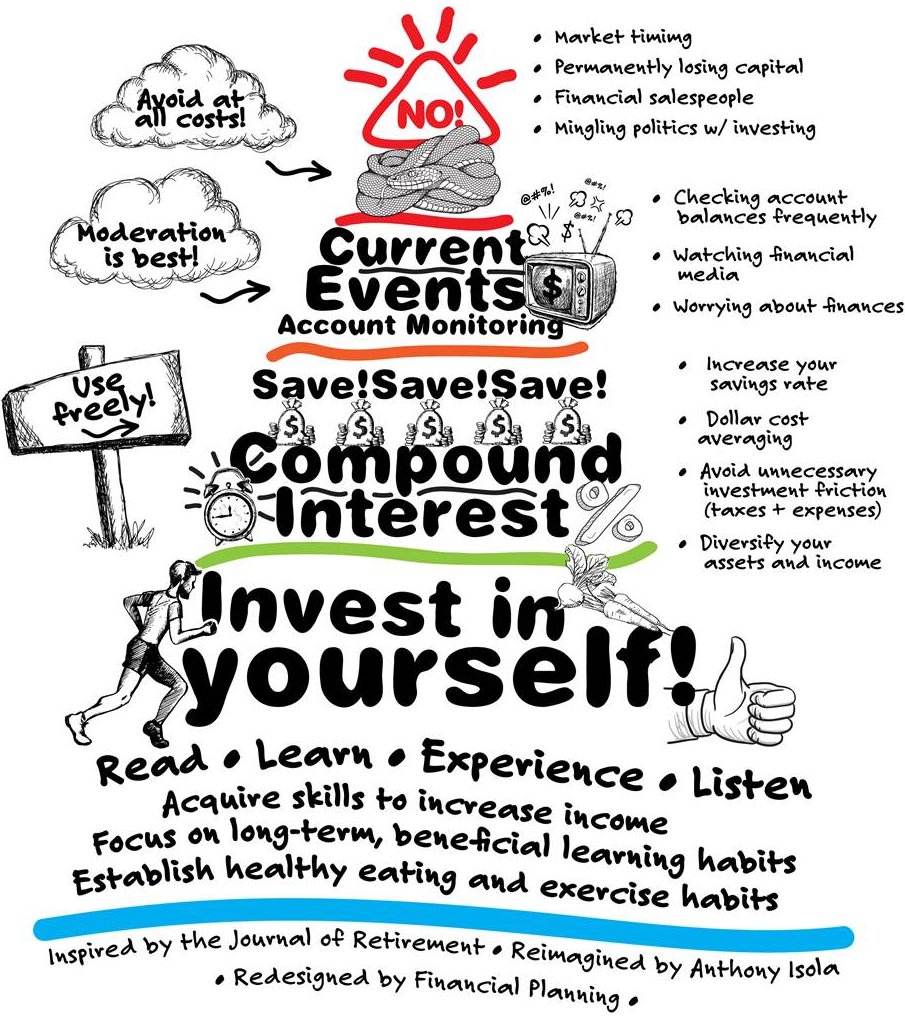

Fantasy gave way to reality; no, I didn’t win the lottery, but I began playing regularly. It seemed one of the few things I could control and it sparked a bit of joy in me. Had I just put some of that money away and invested it, maybe the more fulfilling moments of my life would have arrived sooner. I’ll never know and I’ll never get back that time.

But, I did see a correlation between my lottery playing relative to my overall satisfaction with life; it was an inverse relationship, like a see-saw. The lower I felt, the more I would play. When I felt like I was moving in an upward direction, I didn’t even think about playing; I was excited enough by my life. I had created my very own Misery Index and didn’t even know it.

At the heart of it, I was looking for something that money really couldn’t provide all by itself. Yes, it might have helped speed things along, but it might have derailed me. Misery can be a motivator to make changes; comfort can lead to complacency.

Over the last few days, I read three interesting blog posts from my colleagues. Nick Maggiulli wrote about the life-altering effects of money and why it cannot be measured or predicted by data. Barry Ritholtz wrote about the privilege of taking a thoughtful approach to being productive. Josh Brown wrote about the importance of why we work. All three struck a chord with me.

Nick examines a lottery winner who had already been wealthy; in spite of his savvy and good intentions he implodes and loses everything. This is an interesting twist, as it is typically the rags-to-riches-to rags stories we hear about.

How is it that someone with financial success, skill and knowledge could blow this? Nick analyzes data to draw conclusions and there just isn’t data to predict the human response to the adrenaline rush a windfall can create.

My own personal hunch is that the hunger that led this wealthy man to look for a big win had absolutely nothing to do with money at all. Money is a beautiful, quantifiable distraction when life is unsatisfying. At the end of the day, looking at a big net worth number might take the sting out of the suck of life – but after a while that salve won’t ease what is really causing all that chafing. If life is going off the rails money can speed up the process by miles, and it makes for a wickedly colorful crash and burn.

Barry addresses that by not operating on the gerbil wheel of chasing sales, we are able to slow down and be more deliberate and focused in our efforts as a firm. This leads to a productivity that can be measured in fulfillment, and not merely output for output’s sake. We are how we invest our time. When that is in lock-step what we truly value, life becomes richer – and no, I’m not talking about the green stuff (and yes, it is a privilege).

Josh writes about another one of our colleagues, Alex Palumbo, who didn’t dilly-dally in getting on a career course that has meaning to him. Like many of us, he started out in this industry in a soul-crushing way. Unlike me (and Josh and many others) he got the hell out as soon as he could. He wanted to work at something that had meaning to him and as a result, his career is off to an impressive start.

As Josh points out, “Alex needs a Why, not just a What or a How Much in order to find himself in the working world.”

I would argue we all need this in life – not just in work. Without meaning, it is tempting to fill up on other excitements, such as lottery playing/gambling, boozing, drugging, and cheating, etc.

Having more money isn’t going to ease a dissatisfied life.

That Misery Index can soar off the charts for many reasons; take the time to discover what your reasons are before you buy that scratch-off.