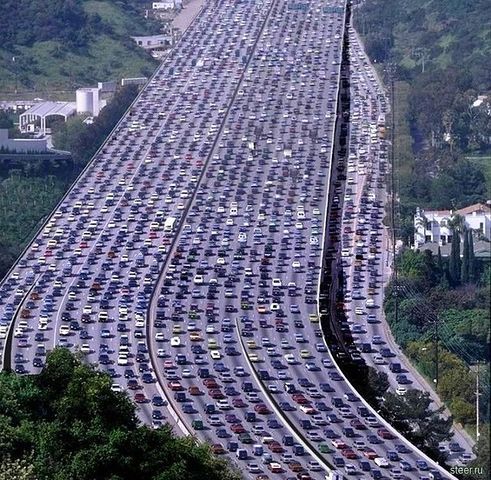

Investing and driving are eerily similar.

Both are dominated by open systems, unknown variables, and irrational human behavior; a recipe for traffic accidents and market crashes.

Tom Vanderbilt’s book, TRAFFIC, describes the chaos of our roads. And, if the word roads is replaced with markets, then we have an excellent description of the daily insanity of global stock exchanges.

“The road is a place where millions of us are thrown together daily in a kind of massive petri dish on which all kinds of uncharted little understood dynamics are at work. There is no other place where so many people from different walks of life, different ages, races, classes, religious genders, political preferences, lifestyle choices, levels of psychological ability – mingle so freely.”

Henry Barnes, traffic commissioner, stated: “Traffic is as much an emotional problem as a physical and mechanical one.”

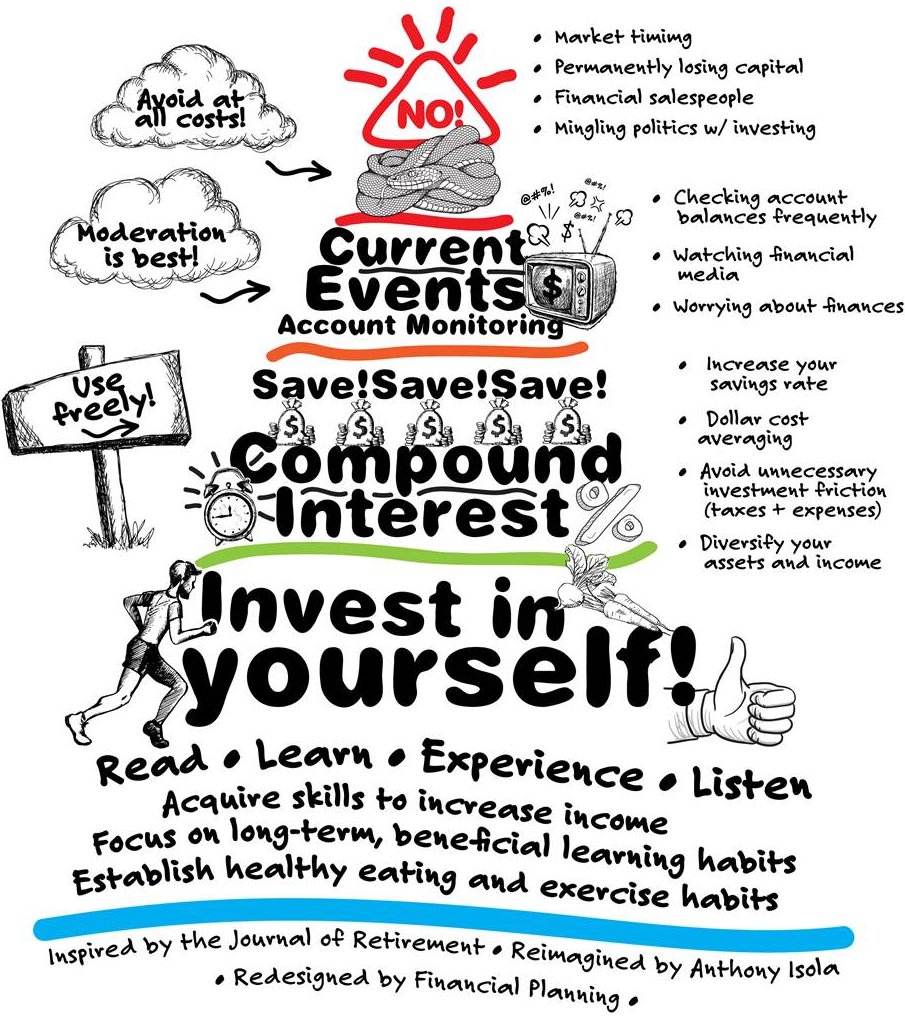

We are often our own worst enemy when investing. Fear and greed are the templates rather than data.

Unpredictable short-term market movements cause us to create mental models and narratives when formulating investment strategies; exemplified in the debate between active vs. passive investing. Some investors swear by hedge funds and alternative assets. Others forsake traditional products and plunge into digital currencies.

“Driving in traffic is no different. According to psychologist, Ian Walker, ‘In a complex system such as traffic where myriad people with a loose sense of the proper traffic code are constantly interacting, people construct mental models to guide them. They just develop their own ideas of how it works. Everyone’s got a different idea.'”

Sound familiar?

Market participants react differently to economic statistics, central bank statements, and political events. If investors had access to data before it was released, there are no guarantees for successful outcomes.

In 2011, the S&P downgraded U.S. Government debt. Most investors would have lost money even if they received this information the day before. Treasuries unexpectedly rallied.

Ian Walker points out. “There are a lot of informal signals on the road. You’ve actually got the half the population taking it to mean one thing and half to mean another – which is crying out for accidents.”

It’s difficult to make split decisions while driving because we are traveling at velocities that we have no evolutionary training for. When algorithms take over the trading floor, we have similar feelings. The Dow plunged 1,500 points at one point a couple of weeks ago, largely due to computer selling. Humans looked in horror at the speed of the descent; not much different than evaluating an unexpected road obstacle while traveling at 70 m.p.h.

We suffer many of the same cognitive deficiencies driving as we do in investing. The endowment effect comes to mind. Once people get something, they find it difficult to give it up; this includes stock their grandparents gave them or a parking spot.

Studies have shown people will take longer to leave a spot when someone else is waiting for it!

Think about optimistic bias. How can we all be better than average investors and drivers? Most think traffic laws are a good idea for OTHERS. The same can be said for active traders who generally produce lower returns than a simple buy and hold strategy.

Just like cars that spend 95% of their time parked, investors should spend most of their days doing nothing.

A big reason we make terrible driving mistakes is we receive little immediate feedback. A DriverCam would verify we avoid accidents because we are lucky, not skilled.

Trading journals perform the same function. Keeping a detailed record of decision processes is a humbling factor for both drivers and investors.

Drivers tend to see only the things they are looking for; this rules out deer and large debris. Investors who purchase products like leveraged ETFs have tunnel vision. They look for 3x the gain but are unprepared for 3x the loss.

Just because drivers have their eyes on the road does not mean they are paying attention.

According to Vanderbilt, “Human attention in the best of circumstances is a fluid but fragile entity.”

Investors have a bad habit of chasing returns. Taxes and fees are not in their line of sight.

Traffic engineers try to create mathematical models involving car flows and accident prevention. These often fail miserably. “Quants” who construct mathematical investing models assuming a closed system find the same results.

“Even the most sophisticated models do not fully account for human weirdness and all the noise and scatter in the system. Traffic engineers will offer caveats…This model does not account for the Heterogeneity of driver behavior.”

Replace the word driver with investor.

Some investors believe robo-advice is a panacea. As long as human beings still have some control over the process, they will be disappointed.

Our roads, like human beings, can never be perfectly programmed.

According to traffic engineer Henry Barnes, “As time goes on the technical problems become more automatic, while the people problems become more surrealistic.”

Think of the way a highway operates. We have a design, vehicle, and driver. Our financial system includes the market, products, and investors.

Who would have thought studying traffic patterns and driving methods would help us become better investors?

Keep your eye on the road and remember slower can sometimes be faster.

Follow these rules and you may end up safer and wealthier.

Source: TRAFFIC Why We Drive The Way We Do by Tom Vanderbilt.