Pensions and bear markets are a toxic combination.

The combination of near-zero interest rates and double declines in stock prices wreak havoc on future promised obligations.

If the teacher’s pensions are an indication of what’s to come, it may be time to prepare for a perfect financial storm.

Young teacher’s pensions and salary stagnation wind up taking up the slack for pension shortfalls.

Most states spare current retirees the pain of reduced checks except for the annual cost of living adjustments.

If history is any guide, this will be the case if market losses continue.

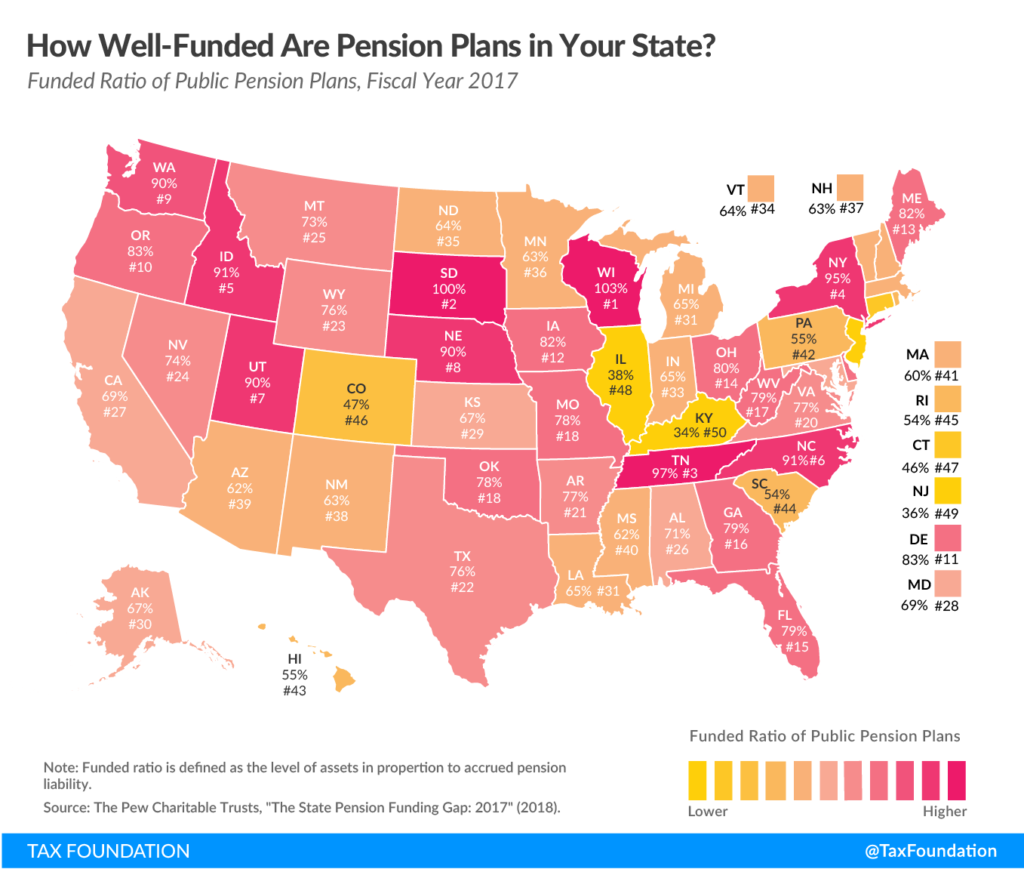

Many states were having trouble funding their pensions before the pandemic.

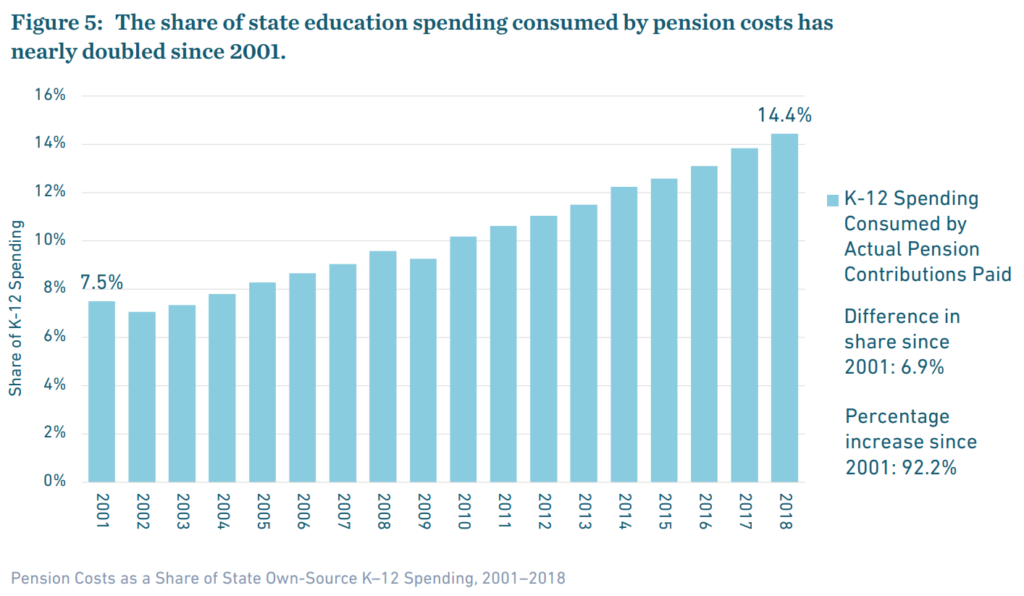

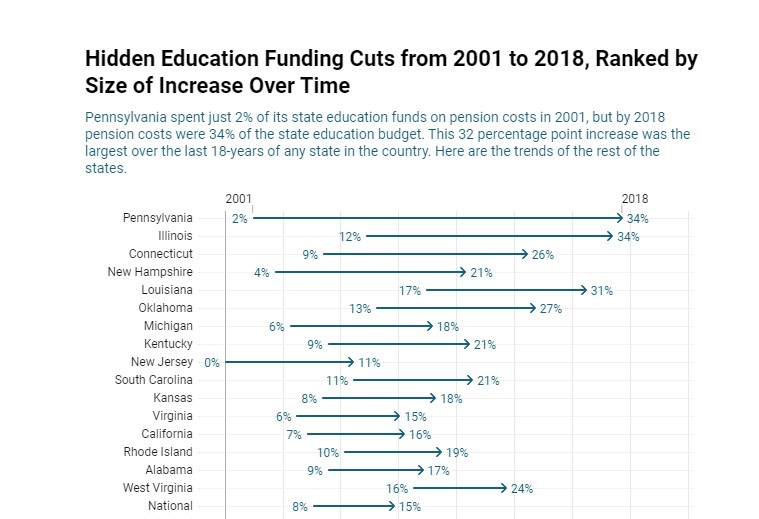

The share of funding going toward pension obligations has almost doubled since 2001.

Most pensions expect investment returns north of 7%. Hitting this aggressive goal is questionable. Even if they do, the future promised benefits could end up falling short.

Market returns don’t occur in a straight line. If bear markets break out during a large generational shift of retired workers – watch out.

Look at what happened to CALSTRS in 2008, the largest teacher retirement plan serving over 650,000 educators.

According to Chad Adleman

In 2008, CalSTRS assumed it would earn 8 percent on its investments. Instead, it lost 4 percent. In 2009, CalSTRS again thought it would make 8 percent. Instead, it suffered a 25 percent decline. After a couple of roller-coaster years, CalSTRS assets declined a total of about 3 percent from 2007 to 2012.

That may not sound too bad, but CalSTRS’s obligations to pay future benefits kept right on growing. From 2007 to 2012, those liabilities grew 29 percent, or about $48 billion.

Between declining assets and rising liabilities, CalSTRS went from being 89 percent funded in 2007 to 67 percent funded in 2012. Its unfunded liabilities — the gap between what it had saved and what is owed to current and future retirees — grew from $19 billion to $71 billion.

Despite these measures, the unfunded liability stood at $107 billion as of last April. Current market conditions widened the deficit.

A combo of higher contribution rates, more sacrifices for new teachers, frozen salary schedules, and less money for classroom instruction are the only way to make the numbers work.

Due to the unfunded liabilities of many states, this is a nationwide trend. From 201 to 2018, pension funding costs occupy a greater percentage of state education budgets.

Static teacher base salaries and wages over this same time confirm the adverse effects of these deficits.

Not every state is in this predicament. New York’s pension system is rock solid. Illinois, Kentucky, Connecticut, and others are in deep trouble.

These statistics highlight the need for low cost, transparent 403(b) plans.

God knows the havoc pandemic related state revenue shortfall will have on these unfunded liabilities.

Raising taxes during a recession isn’t an option.

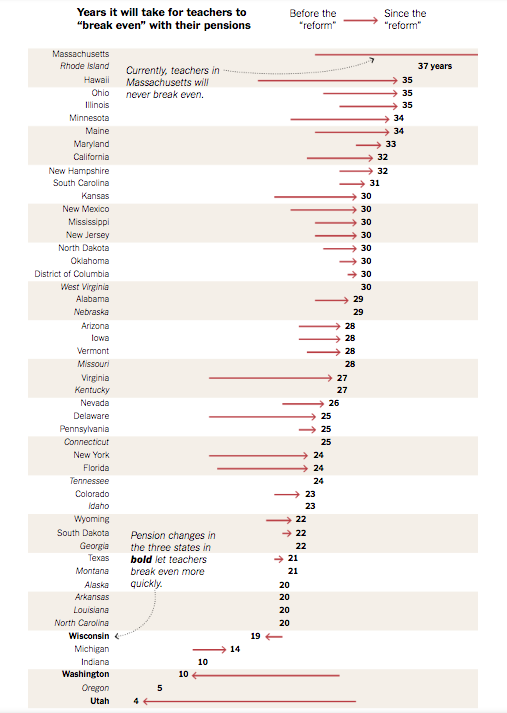

Young teachers shouldn’t have to pay for the mistakes of past generations with reduced benefits. Only about a quarter of new teachers can expect to break even on their pensions.

Source Bellwether Education Partnership

Pensions are vital to the retirement prospects of our nation’s public school teachers. In some states, tough choices lay ahead to fulfill these promises.

The first step toward making teachers retirements secure is reforming the sorry state of their defined contribution plans.

Grabbing the low hanging fruit by transforming teacher’s 403(b)s into cheaper and more transparent options is a no-brainer.

Its time to harvest the crop.

Teachers and other public employees have little control over state budgets.

Contributing to a low-cost 403(b) plan is a right, not a privilege.

The next set of decisions won’t be nearly as easy.