Why do investors incinerate themselves in the financial markets?

It’s not intentional. They’re wired to self-destruct for reasons beyond their control.

Look at the moth’s behavior. of moths, flying into the flames of lit candles.

Is this self-immolation a deliberate suicide over a lover’s quarrel?

Nope, Moths making burnt offerings of themselves exhibit complex reasons for their bizarre flight patterns.

Their actions are a by-product of something complicated.

Artificial light is a recent entry into the travel itinerary for flying insects.

Bugs use things like the sun and the moon to keep them on course. They rely on celestial objects to navigate the sky. This enables them to return home, using a certain angle to keep them on course.

Problems arise when things like candles appear in their field of vision. The same angle for navigating by the stars causes them to fly into the flames and commit an apparent suicide.

Surprisingly, what they’re doing makes perfect sense.

According to Richard Dawkins:

We don’t notice the hundreds of moths silently and effectively steering by the moon or a bright star or even the glow from a distant city. We see only moths wheeling into your candle, and we ask the wrong question: Why are all these moths committing suicide? Instead, we should ask why they have nervous systems that steer by maintaining a fixed angle to light rays, a tactic that we notice only when it goes wrong. It never was right to call it a suicide. It is a misfiring byproduct of a normally useful compass.

We should ask the same question when watching investors make burnt offerings of their portfolios.

Do they really want to commit financial suicide, or is this just a misfiring of a normally useful compass?

My colleague Barry Ritholtz is on to something.

In discussing family trauma and consequent attitude toward risk, he states:

Psychologists have long known that stressful early life family disruption has long-lasting effects on an individual’s personality. What is less well known is the impact those traumas have on risk-based decision-making later in life.

Trauma impacts the lives of many Americans. Forty percent of children experience a divorce. Five percent suffer the loss of a parent.

They grow up and invest in the market. Making risk decisions that seem illogical to the casual observer. Unbeknownst to critics, their troubled childhoods or some other trauma helped shape their asset allocation strategies.

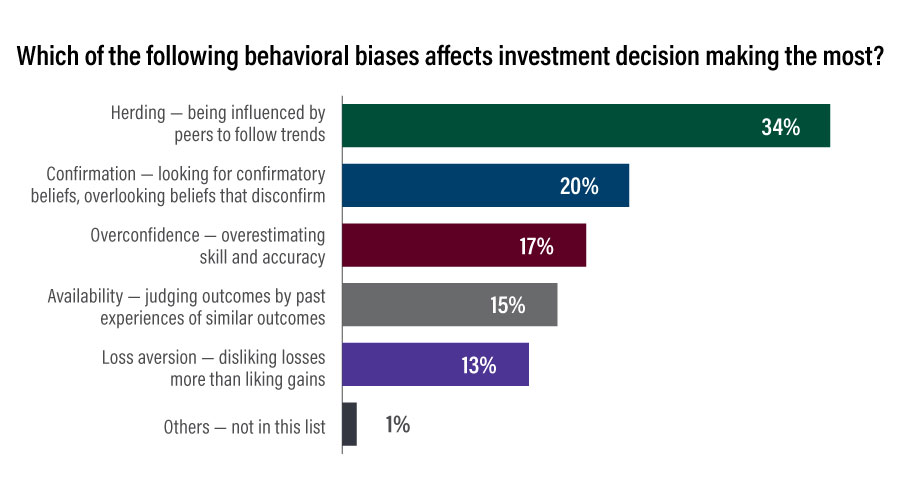

Source CFAinstitute.org

Investors sell at market bottoms or keep their long-term investment funds in cash for reasons that go far beyond money management theories.

The problem magnifies when they don’t understand why.

Ritholtz goes on to say:

Learning about our cognitive operating system’s inherent biases and predilections is useful for investors. At the very least, it allows you to avoid some of the more obvious errors. It gets much trickier when an investor considers personal childhood traumas and other subjective events.

The next time you observe a moth self-immolate or an investor Napalm a financial plan during a market downturn, don’t jump to conclusions.

They’re using the right compass but for the wrong reasons.