College isn’t the right track for many young people; there, I said it.

Before lighting a fire to burn me at the stake, let’s look at some data:

- 20% of students don’t graduate from high school.

- 20% will go from school to something besides further schooling.

- 20% enroll in college but fail to graduate.

- 20% graduate but land in jobs that have very little to do with their (often) very expensive degrees.

“College for all” shouldn’t be the goal of the American educational system the way it’s currently configured.

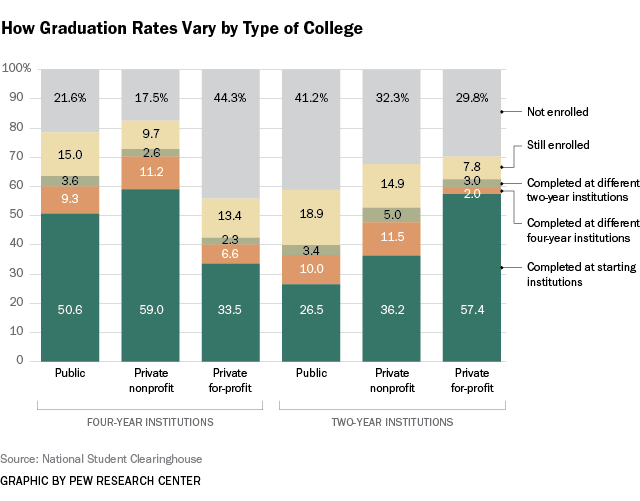

The data further challenges our current system with these striking numbers. About 40% of students in four-year colleges graduate from their first school on time. Two-year schools show worse numbers. Only 30% receive their diplomas after three years.

According to Oren Cass, author of The Once and Future Worker, we get the worst of all worlds. “Policymakers ignore the importance of a healthy labor market for workers lacking postsecondary education by instead claiming universal college completion as a plausible goal- even though it has proven implausible for most Americans.”

“College for all” became the mantra starting in the 1960s. High schools abandoned a tracking system for less academically-oriented students which, in the past, steered them toward vocational training to become plumbers, electricians, mechanics, welders, machinists and other technicians.

Committing most students toward a single college-bound track defies logic. It has failed a multitude of young Americans.

College was never designed for the majority. Even during the post-World War II period, only 20% of men between the ages of 18-24 attended college; this despite the enormous benefits of the G.I. Bill.

Cass states, “It would be an extraordinary coincidence if a program designed decades, if not centuries, ago for the edification of the wealthy and the training of a narrow segment of the population also happened to meet the needs of the typical 21st-century workforce entrant.”

As recent scandals displayed, some high-priced colleges today would rather appeal to parents’ egos rather than the attainment of high-quality jobs for their children. Others proudly proclaim the Instagram readiness of their institution.

Predatory for-profit schools are obviously not the answer.

We can do better than this.

Many students leave The K-12 space completely unprepared to succeed in a college environment. We are setting these young people up to fail and, more importantly, not giving them an option to acquire a decent paying job given their skill sets.

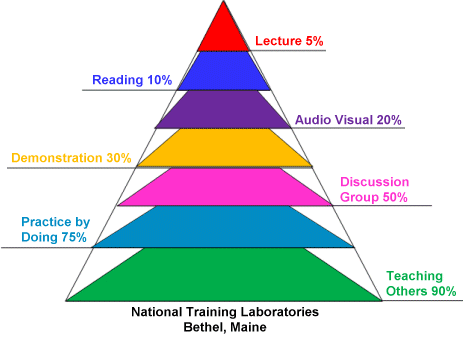

Everyone learns differently. It doesn’t mean a student is less intelligent because they aren’t capable of sitting through lectures and passing a written exam.

We need to face the fact each student follows a different path to success. A four-year college degree may not be their ticket to reach their full potential. There’s nothing wrong with this outcome.

Often, so-called blue-collar jobs are derided in the media and other places as being a sign of failure or incompetence. Having their child work in a trade isn’t something many parents like to brag about to their friends. We need to change this perception – fast.

GPAs shouldn’t define self-worth.

To quote Seth Godin:

“The easiest way to get someone’s attention is to compare them to someone else. When people compete on the same metrics (how many followers, how much income, how many points scored) the focus gets very tight. With a simple metric, there’s no confusion at all about how to earn more status. The irony is that the simpler the metric, the less useful the effort is. Big ideas, generous work, important breakthroughs–to pursue these goals is to abandon the metric of the moment in favor of a more useful sort of contribution. If we want smart kids, the GPA is a lousy way to get them.”

While service jobs make up the majority of our workforce, we all can’t serve frappuccinos to one other.

Despite having a master’s degree, I am so spatially challenged it’s almost laughable. I watch in awe when service people or relatives make vital repairs in my home. Putting something together in my home produces lots of blood, sweat, and tears. Along with dozens of “extra parts.”

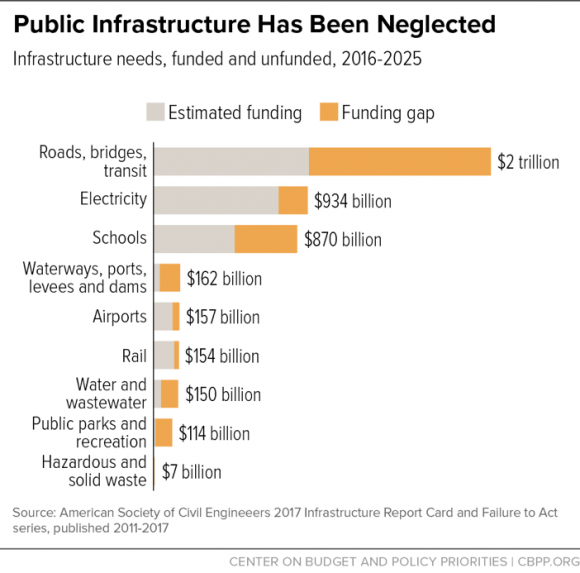

We desperately need people to produce and maintain things; our decrepit infrastructure is literally begging for these workers.

No one is saying to abandon these students. On the contrary, there are many proven solutions already out there to educate them by focusing on their strengths.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) concluded most developed countries have between 40-70% of secondary school students in vocational or technical programs (excluding the U.S.).

The road won’t be easy but it will pay gargantuan dividends. For many high school students, academics would need to be compressed, emphasizing practical skills with opportunities to explore various industries. Classroom learning equally divided with apprenticeships sponsored by vetted private companies would replace the standard eight-period day.

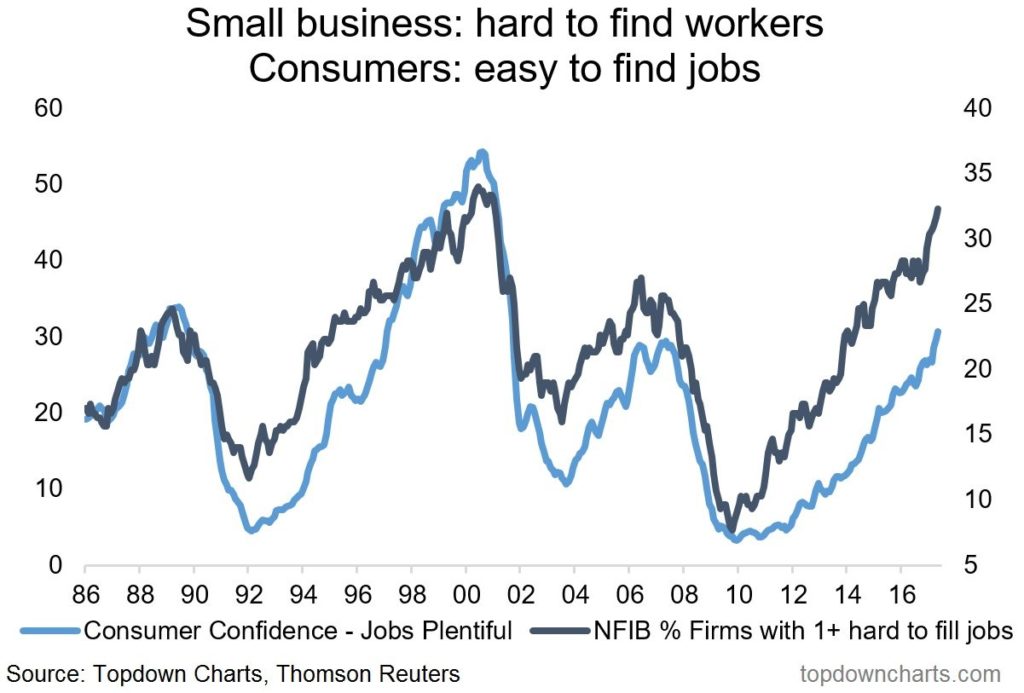

Corporations vociferously complain about a lack of qualified workers. Here is their chance to step up to the plate and put their money where their mouth is.

Many developed nations offer proven examples of how this could work.

“In Switzerland, roughly 2/3 of students go the vocational route, choosing from more than 200 occupations. A 3-4 year program begins in the 10th grade, with students splitting time between employers, industry groups, and the classroom. Germany’s apprenticeship system offers recognized qualifications in 350 occupations and 80 per cent of its young adults are employed within six months of completing their education, compared with 48% in the U.S.”

The New York Times remarked, “It is not uncommon to find executives in Europe who got their start in apprenticeships.”

We could modify programs like these to fit our cultural needs and the unique aspects of our labor market.

In addition, there is a massive disconnect between college administrators and the perceptions of parents paying the bills. College presidents have worthy and idealistic goals regarding making students life-long learners and educated citizens. But this view clashes mightily with the aspirations of most parents.

Terry Hartle, of The American Council on Education, sums up their view: “As for the general public, often all they care about is jobs.”

While teaching public school for over 20 years, I saw much of this data in real time, I have always felt only about 25-30% of the students I taught would maximize their potential at a four-year university. The rest needed another path to bloom.

Often I would appoint struggling students as my Chief Technology Officers. Most couldn’t do well on standardized exams but they could fix stuff – for me and their honor roll classmates. Despite these skills, they followed an inappropriate track, playing to their weaknesses rather than strengths.

I have many family members and friends who went to college but aren’t doing anything related to their degree. The four years they devoted to this quest would’ve been better spent in a specific internship program devoted to their chosen fields. They are doing very well but would be doing better if they were offered an apprenticeship program instead of peer pressure to attend schools that didn’t fit their abilities.

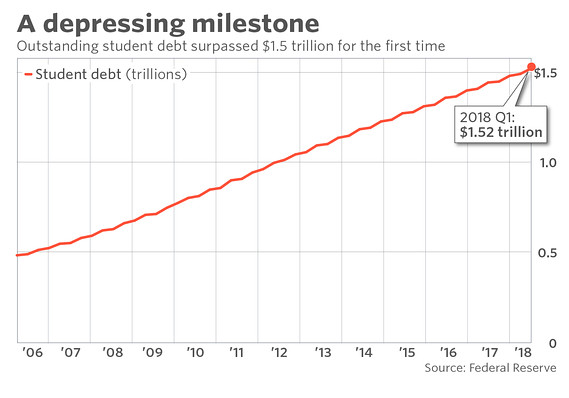

Emerging debt-free and hitting the ground running into a well-paying job is a terrific way to start a career.

Many students attending expensive colleges would succeed anyway because of family connections and other matters beyond their control.

Nick Hanauer’s pointed article in The Atlantic states: “Even the most thoughtful and well-intentioned school reform program, can’t improve educational outcomes if it ignores the single greatest driver of student achievement: household income.”

Reforming our current “everyone should go to college” system gives America a chance to break the wheel fueling inequality. If future graduates attain well-paying jobs through vocational and apprenticeship programs, the next generation will have a fighting chance to move up the social ladder.

Career tracks need to be given the respect they deserve both socially and monetarily. It would be interesting to see how well-designed vocational and internship programs along with changed public perception would change these charts.

Estimated lifetime earnings by educational attainment (in millions of dollars)

Source: Tamborini, Christopher R., ChangHwan Kim, and Arthur Sakamoto. 2015. “Education and Lifetime Earnings in the United States.” Demography 52: 1383–1407.

Cass makes a thought-provoking closing argument: “The education system should commit to spending at least as much on a 15-year-old whose next seven years will be spent in a combination of school, apprenticeship, and employment as it spends on one headed to a four-year public university.”

Around 80% of young people and their parents couldn’t agree more.

Source: The Once and Future Worker by Oren Cass