Investors are often no better than a pack of chimps protecting their banana supply from their rivals. Six million years of history has ingrained this behavior in all of us. “Beware of hostile groups” runs through our veins just as much as flowing blood.

The Nurture Assum ption, by Judith Harris, gives a brilliant description of why it is in our DNA to join a tribe. The biggest reason is, according to Harris, “It takes a ‘them’ to make an ‘us.’”

ption, by Judith Harris, gives a brilliant description of why it is in our DNA to join a tribe. The biggest reason is, according to Harris, “It takes a ‘them’ to make an ‘us.’”

Finance clans are no different. We have groups advocating the following: Active vs. passive investing; Bears vs. Bulls; Austrians vs. Keynesians; along with assorted other hordes of conflicting beliefs to round out the menagerie. The one thing many of these financial extremists have in common is, like the man with a hammer, every problem is a nail.

Another commonality they share is an unbending belief that they are right. Unfortunately, only a few are; this is in probability of success, not certainty. Defying all logic, the more evidence that is presented to the misinformed divisions, the more entrenched their views become.

Why do these tribes persist in this self-defeating behavior? The answer: it’s complicated. We inherited these tribal traits from our primate ancestors. In ancient times, the group was our best hope for survival in a very dangerous world .This carries over to investment tribes.

The power of the group is vastly underestimated. Our children’s friends have much more influence on them than we realize. “Kids often learn how to behave by identifying with a group and taking on its attitudes, behaviors, speech, and dress,” according to Harris.

Most children rarely bring family customs into a group. Unfortunately, they will bring their friends’ habits into the home. There is a reason a parent maybe spending their days trying to catch a Jigglypu!

This begins at an early age. Children in nursery school are often attracted to other toddlers just like them.

Peer pressure from groups will often cause an individual to “Question the evidence of his own yes before he will question the unanimous opinion of his peers,” says Harris.

The group is unified by the presence of other tribes. Its saliency increases when outside danger is detected. According to Harris, “Intra-group power struggles and rivalries are swept under the rug when another group appears on the horizon.” This is true for both humans and apes.

This explains a great deal about investors’ behaviors. The mere presence of a rival will make the groups’ investing belief stronger, no matter how misguided. Think of Fidelity’s Chairperson, Abigail Johnson, insisting index funds are a fad. Her belief only became stronger by the presence of her rivals at Vanguard. With her tribe threatened, she dug in her heels.

During the tech bubble, many technology stock maniacs (I mean, enthusiasts) became even more radicalized in their views when value investors, like Warren Buffett, questioned the insane valuations of these companies. They banded together and purchased more Pets.com on margin, despite the fact a tidal wave was about to engulf them.

The mere presence of opposition galvanizes and unites the tribe. Harris points to the infamous Donner Party, who became cannibals when they were trapped in a Sierra Nevada Mountain winter on their journey to California.

Harris speculates maybe they would have survived if there were Native Americans or other pioneers nearby to threaten them. Without any opposition to unify them, they literally ate each other!

Investing is one of the worst environments to have a close-minded, tribal attitude. Complex problems cannot be solved by unthinking bands. Investing is a very fluid, open system that draws its energy from unpredictable variables based upon human emotion.

Your tribe may insist on inflation, when there is none to be found. They may constantly be seeking the next Black Swan while never giving their money a chance to grow. They may foolishly try to time the market, constantly selling low and buying high. Inadvertently, they end up fighting the last war.

The kicker is the more their theories are confronted by data, the bigger bets they tend to place. The tribe circles the wagons to protect themselves from their perceived rivals.

What is the answer if we are genetically predisposed to join a tribe?

The answer is: find the right one! I know I have.

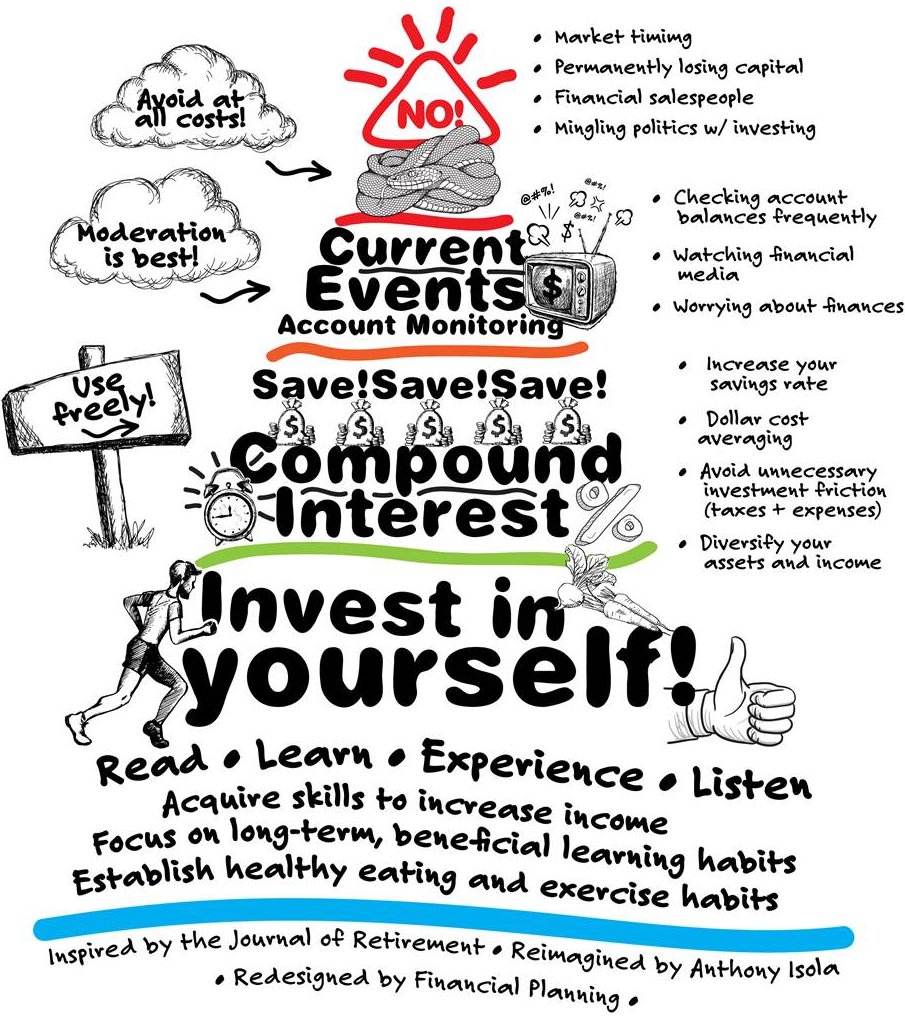

Your tribe, like mine, should consist of people of high character. Data and evidence should take precedence over emotion. The focus should be on what the tribe can control. Things beyond the tribe’s influence are rightly ignored.

Investment friction, like taxes and high-fee products, along with global diversification, are prime examples of the former; short-term market returns, the latter.

Finally, your tribe should think in probabilities and not certainties, which are non-existent in the markets.

Unfortunately most investors end up in tribes that spend their time throwing coconuts at each other, like our ancestral primates. They worship false investment gods and create cults of personality.

Deal with it; tribes are a major influence upon the choices we make. Joining the right one to manage your investments is a decision you should not take lightly.

[…] Why are Investors so Tribal? (tonyisola) […]

[…] Why are investors so tribal? (A Teachable Moment) […]

[…] financial advisor Tony Isola wrote this week about the downsides of similar minds flocking together on the Internet, before […]

[…] financial advisor Tony Isola wrote this week about the downsides of similar minds flocking together on the Internet, before […]

[…] If home country bias is a macro manifestation of our tribal desires, then a more micro view will show other tribal divisions at work in the investing world. The problem with a tribal approach is that adhering to a group requires an investor to turn off their rational brain in order to maintain coherence with the group. A common example is the so-called “gold bugs,” who see gold prices rising no matter the economic scenario. As Tony Isola writes: […]

[…] If home country bias is a macro manifestation of our tribal desires, then a more micro view will show other tribal divisions at work in the investing world. The problem with a tribal approach is that adhering to a group requires an investor to turn off their rational brain in order to maintain coherence with the group. A common example is the so-called “gold bugs,” who see gold prices rising no matter the economic scenario. As Tony Isola writes: […]