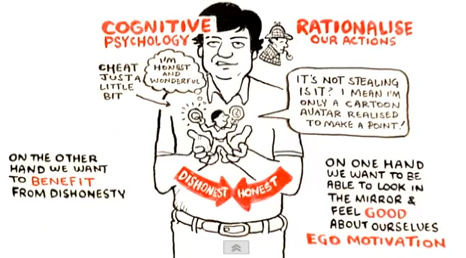

The proposed new rule from the Department of Labor requires brokers to look out for their clients’ best interests in retirement accounts. Unfortunately, making financial salespeople disclose all of their obvious conflicts of interests may not be enough to stop their bad behavior.

An excellent book written by Dan Ariely called The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty explains why full disclosure may not solve the problem of high fees and inappropriate investments sold to many investors. As the author states, “In fact, disclosure can sometimes make things worse.”

An experiment was conducted which included two groups: estimators and advisors. The estimators had to guess how much change was in a jar. The advisors were to give guidance to the estimators on making a proper guess.

The estimators were only allowed to view the jar from a distance. The advisors were permitted to see it up close and were given an accurate range of the value of all the coins in the jar.

Three conditions were then enacted. The control portion of the experiment paid the advisor on the accuracy of the estimator’s guesses. In this case, there was no conflict of interest for the advisor to mislead the estimator.

The second condition paid the advisor more if the estimator overvalued the coin total. This was an obvious conflict of interest for the advisor to overstate the value of the coins.

The third condition paid the advisor more the larger the error in the estimator’s guess. The kicker was the advisor had to disclose in advance that he would receive higher compensation the more the estimator over-guessed.

In the third situation the estimator could take the advisors recommendation and discount it appropriately due to the advisor’s obvious, and fully disclosed, conflict of interest.

The results were predictable in the first and second conditions. In the first condition, the advisor and estimator worked together to determine the appropriate amount of coins, since they would both be rewarded for accuracy. This is similar to a fee-only Certified Financial Planner working with a client under the fiduciary standard.

The second condition, in which the advisor was compensated more if the estimator over-guessed, was also predictable. The advisor made sure he gave advice which inflated the total coins in jar and earned him a commission. This is not unlike incentives for brokers to sell Class A mutual funds and expensive variable annuities to their unsuspecting clients.

The third condition was most fascinating. Even though the estimator knew the advisor had obvious conflicts, which were fully disclosed, the advisor still earned a bonus for influencing the estimator to make an overly large guess for the coin total.

The estimator reduced the advisor’s recommendation knowing he was being paid to inflate the total amount of coins in the jar. The problem was it was not discounted enough!

The estimator did not subtract nearly enough from the coin total and “did not sufficiently recognize the extent and power of the advisors’ conflict of interest.” In other words, full disclosure in a very conflicted sales model does not benefit the client.

The results of this experiment can be directly applied to a broker-centered financial services service model.

Even if brokers fully explain their conflicted sales process to their clients, it may not be enough. The client will still be at a significant disadvantage and will most likely under-discount the price they will pay for an investment product.

The salesperson will still be able to over-charge, even though the client was told this was his intent.

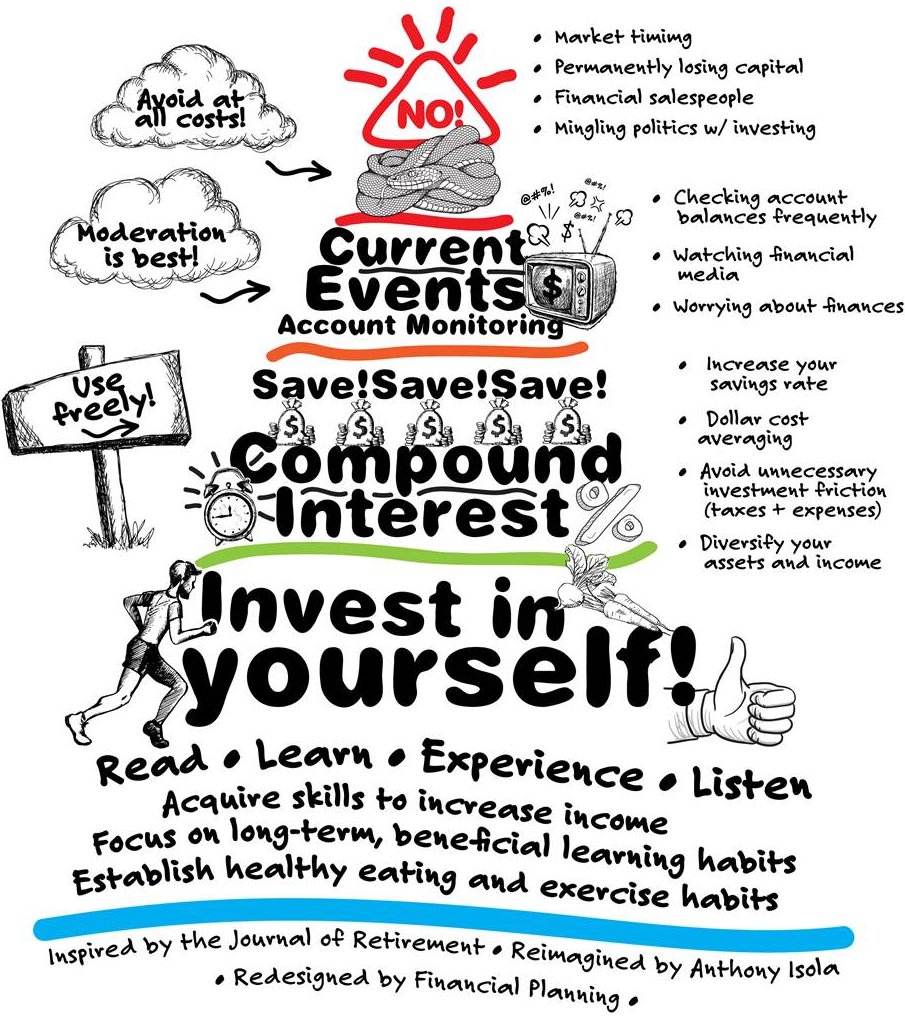

Eliminating conflicts of interest may not be solved by full disclosure. The only real way to attack this problem is to align investors’ interests with their financial advisors. This can be done in a variety of ways.

Paying by the hour or on a retainer fee will help align client/advisor interests. Charging a reasonable percentage based on client’s assets under management can also do the trick.

These experiments display the fact that as long as there are competing interests in the advisor-client relationship, the client will end up losing. Practices such as revenue sharing, front-end loaded mutual funds, sales quotas, kick-backs, stock based loans, and prizes like free cruises will seldom benefit the investor. This is true even if they are fully disclosed and explained.

If these types of incentives are not removed, it will not matter how truthful advisors are with their clients regarding full upfront disclosures. At the end of the day, the conflicted salesperson will still win. Their winning hand is to the tune of about 17 billion dollars in unnecessary investment fees, annually.

Unfortunately human nature cannot be changed. We all respond to incentives no matter how perverse they might be. Ironically, telling the truth can still make some people dishonest.

[…] Why full disclosure isn’t always enough (A Teachable Moment) […]