The way the current Stock Market Game is constructed does more harm than good. Winning teams are rewarded for concentrated portfolios, excess leverage, and short-term reactive behaviors. Winners are determined by chance, since many of the games only last for 10-15 weeks.

The bigger danger lies in the fact the victorious teams may actually think they know what they are doing and apply these methods to the management of real money.

Jason Zweig pointed this out in his Wall Street Journal article “Teaching the Wrong Lessons.” He correctly observed, “If your own children are studying the stock market in school, you had better ask them what they have been learning. They might need to be deprogrammed.”

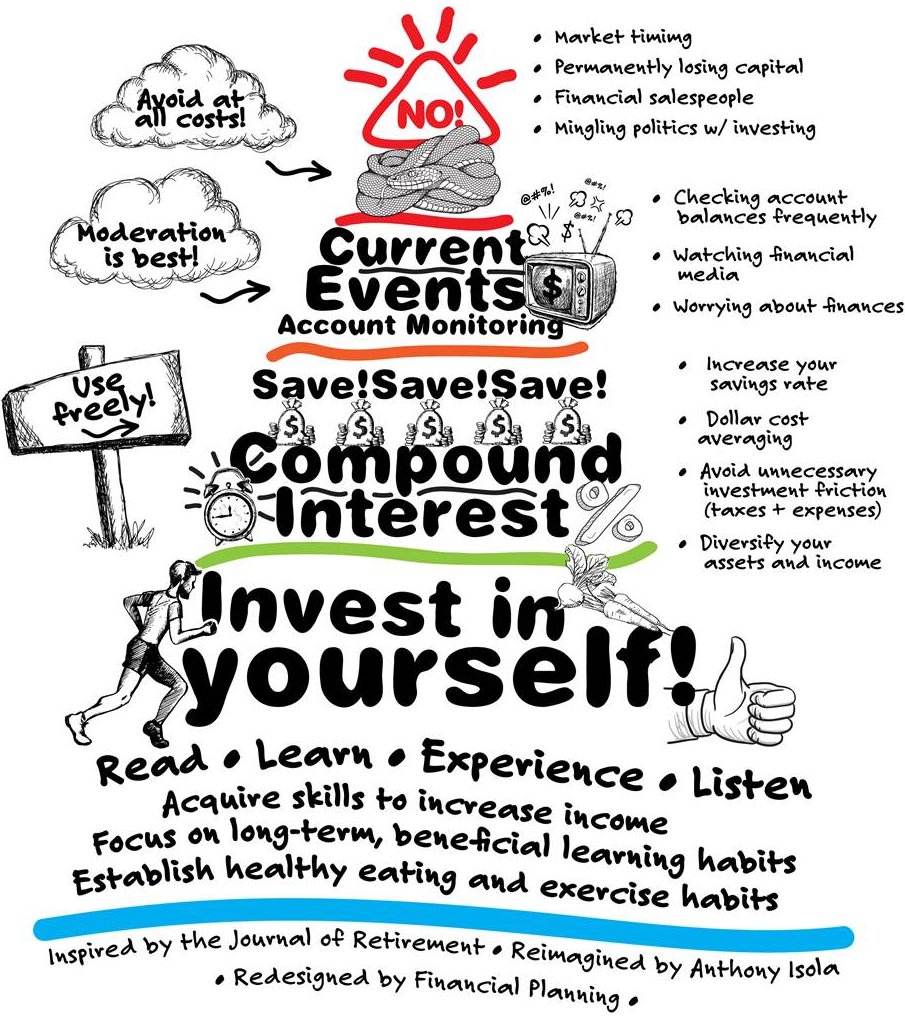

I have a unique perspective on this matter. Unlike Mr. Zweig, I was the Stock Market Game Coordinator for many years where I taught, at a middle school in Plainview, Long Island. While I was running the game, I earned my CFP and created my own fee-only RIA firm that is based upon comprehensive financial planning, low-cost index funds, and investing for the long term.

Running the game forced me to violate all the investing principles I had painstakingly learned over the years. I was forced to guide the students into the dangerous world of short-term speculation, which I knew all about from my former days as a currency trader.

We were very successful in this game. We won just about every year. I joked with the school’s principal that our goal was to be “banned from the game” just like the expert Black Jack players that are so hated by casinos.

We won by using leverage. We borrowed 50% on our portfolios, which were initiated at $100,000. We often used triple leveraged funds which gave three times the return of the asset class we selected. In effect we were playing with $400,000 while the other schools had a measly $100,000 to gamble with.

If things blew up we lost nothing. If we were correct, we became heroes (not too much different than the mortgage-crazed bankers from the good old days).

We won once by going short gold and silver. We often bought triple leverage funds in volatile asset classes like emerging markets, foreign currencies, and financial stocks during the great recession. Our greatest trade was going short the VIXX (which tracks market volatility) during the height of the financial crisis. We sold it short at 80, which I believe was its peak.

I felt bad when kids would ask me if they could buy IBM or McDonalds. I told them they could, but owning stocks that “move” are what win the game. We never bought more than three positions and leveraged them up big time! I tried to tell them that what we were doing was just the opposite of what you should do with real money. We just got caught up.

We wanted a day off from school so we could go get our medal and have our picture taken for the district newspaper. Before 9/11, the ceremony was at the NYSE, which was pretty cool. Later on, we had to settle for local colleges and “a make your own sundae bar.”

I would often laugh to myself when high school kids talked about the rationale for their brilliant winning strategies. I could save them a lot of time by replacing their speeches with a four letter word: LUCK!

The incentives to win the game were perverse. This is not unlike the justifications many retail brokers make when they sell their unwary “customers” expensive, under-performing investment products. They do it to win and make the big money and go on fancy cruises. If the incentive is big enough, people will rationalize just about anything.

We won water bottles and gift bags. The kids missed a few periods with a cranky teacher. I was appointed the school’s investing expert. The administration and parents were happy. Life was great!

Looking back on those days, I hope the students listened when I told them what we were doing was wrong. Though everybody was happy with our results, I am afraid they taught all the wrong lessons.

[…] not the first person to complain about this stupid school-sponsored game. Here’s confessions of a stock market game winner. Here’s someone at the WSJ complaining about how it teaches exactly the wrong […]

[…] the game forced me to violate all the investing principles I had painstakingly learned over the years. I was […]